A digital human knowledge and action network of health workers

Challenging established notions of learning in global health

When Prof Rupert Wegerif introduced DEFI in his blog post, he argued that recent technologies will transform the notions and practice of education. The Geneva Learning Foundation (TGLF) is demonstrating this concept in the field of global health, specifically immunization, through the ongoing engagement of thousands of health workers in digital peer learning.

As images of ambulance queues across Europe filled TV screens in 2020, another discussion was starting: how would COVID-19 affect countries with weaker health systems but more experience in facing epidemic outbreaks?

In the global immunization community, there were early signs that ongoing efforts to protect children from vaccine preventable diseases – measles, polio, diphtheria – would suffer. On the ground, there were early reports of health workers being afraid to work, being excluded by communities, or having key supplies disrupted. The TGLF quickly realised it had a role to play in ensuring that routine immunization would carry on in the Global South during the pandemic and then to prepare for COVID-19 vaccine introduction.

Peer learning vs hierarchical, transmissive learning models

Since 2016, TGLF had been slowly gaining traction in the world of immunization learning, with its digital peer learning programmes for immunization staff. These programmes reached around 15,000 people in their first four years, before the pandemic, about 70% of whom were from West and Central Africa, and about 50% of whom work at the lowest levels of health systems: health facilities and districts.

The TGLF peer learning programmes were developed as an alternative to hierarchical, transmissive learning models, in which knowledge is developed centrally, translated into guidance by global experts, which is then disseminated through cascade training.

In the hierarchical model, health workers are merely consumers at the periphery of the process. COVID-19 brought the inadequacies of this approach into sharper focus, as health workers dealt with challenges that had not been foreseen or processed through existing guidance.

No technical guidance could address every scenario health workers faced, such as reaching the most marginalised communities or engaging terrified parents at a time when science had few reassuring answers. They needed to be creative and empowered to find their own solutions. Health professionals learned to rely on each other as peers, learning from each other how to negotiate many unknowns, without waiting for the answers provided by formal science.

The TGLF approach quickly demonstrated its usefulness in connecting peers during the pandemic. In 2020, the number of platform users doubled to 30,000 in just six months (compared to four years to gain the first 15,000 users) and has now trebled to 45,000.

Adoption doubled from 15,000 pre-pandemic users to 30,000 users in the first six months of the pandemic. It now stands at 45,000 in 2022.

Addressing Covid-19 impacts through challenge-based learning

The foundation of the TGLF approach was the COVID-19 Peer Hub, an 8-month project based on challenge-based learning, which challenged individuals to give and receive feedback as they collaborated to:

- Identify a real challenge that they were expected to address in their everyday work

- Carry out situation analysis, and

- Develop action plans that are peer-reviewed and improved.

The Peer Hub was inspired by the works of several of academics who helped create the Foundation: Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis, and their technological implementation of “New Learning;” George Siemens’ learning theory of connectivism; and Karen E. Watkins and Victoria Marsick’s insights into the significance of incidental and informal learning.

The Peer Hub demonstrated the creation of a “human knowledge and action network” formed through both formal and informal peer learning combined with ongoing informal social learning between participants. The network was built on the principle that participants were themselves experts in their own contexts, and creators, rather than consumers, of knowledge. Front-line health workers suddenly had the legitimacy and ability to share experiences with their peers and experts from around the globe.

In the first ten days, COVID-19 Peer Hub participants shared 1224 ideas and practices through the Ideas Engine, an online innovation management tool.

Results of peer-led, challenge-based learning interventions

More than 6,000 health workers joined the TGLF COVID-19 Peer Hub, where they:

- Documented and shared 1,224 practices and ideas to maintain routine immunization through the Ideas Engine;

- Developed 700 peer-reviewed action plans, informed by ideas and practices shared through the Ideas Engine;

- Learned to support each other in implementing these plans during a four-week “Impact Accelerator Launchpad;”

- Responded to concerns about vaccine hesitancy in the face of COVID-19 vaccine introduction, by developing a peer-reviewed case study documenting a situation in which they had helped an individual or group overcome their initial reluctance, hesitancy, or fear about vaccination. The resulting qualitative analysis – unique in accessing so many firsthand narratives from health workers – was produced by 734 participants.

Assessing the value of peer-led learning in a global vaccine education programme

The next challenge for TGLF was how to document and capture the value of this? Most of what was shared between peers was not new or innovative at a global level – but this did not make it less useful to the individual practitioner who had not encountered it before. How to account for the sense of identity, community and solidarity arising from peer learning that gives health workers the confidence and motivation to try new things? How to make a link between investment in peer learning, and children immunized?

“Participation in the Peer Hub has motivated me to organize my district to implement actions developed. It has also encouraged me to invite many Immunization Officers to learn the experiences from other countries to improve country immunization sessions”

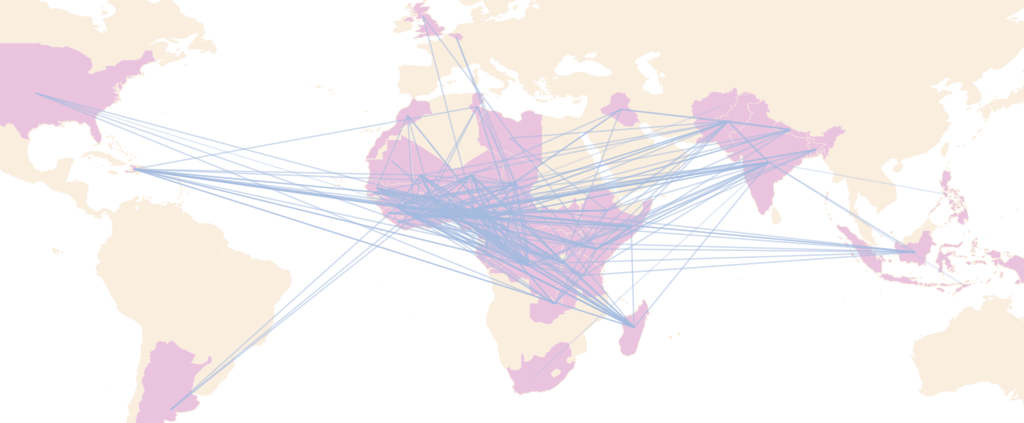

Tracking movement of practices and ideas shared through the Ideas Engine between countries

Because while health workers responded positively to opportunities to connect, learn and lead with one another, TGLF is very much a new entrant in a well-established institutional learning environment for global health. Here are some questions we’ve developed as TGLF challenges established norms and ways of working:

- How would you feel as a global expert if you were asked to give up your role as ‘sage on the stage’ to be a ‘guide on the side’ to thousands of health workers?

- Can self-reported data from thousands of health workers evaluated by peers be trusted more or less than a peer-reviewed study?

- What does ubiquitous digital access mean for training programmes that have previously incentivised learner participation in face-to-face events through payment?

“I can actually broaden my vision and be more imaginative, creative towards new ideas that have come up to improve overall immunization coverage.”

Working with DEFI and other similar institutions, TGLF looks forward to:

- Exploring and demonstrating the credibility of what we do through critical independent research and commentary

- Demonstrating the potential of our approaches to large institutions and their donors;

- Developing a bigger picture of how other sectors are adapting to the affordances of digital learning technologies;

- Meeting others innovating in digital learning to be inspired and cross fertilise.

We look forward to fruitful dialogues!

Ian Steed

Associate, Hughes Hall

Ian works as a consultant in the international humanitarian and development sector, focusing on the policy and practice of ‘localising’ international aid. In addition to his work with TGLF, Ian is involved with financial sustainability in the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement and is founder and board member of the Cambridge Humanitarian Centre (now the Centre for Global Equality). He studied German and Dutch at Jesus College, Cambridge, and has lived and worked in Germany and Switzerland.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks